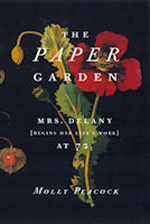

| Molly Peacock is a poet, essayist and creative nonfiction writer. She has published six volumes of poems including Cornucopia: New and Selected Poems and, most recently, The Second Blush (both from W.W. Norton and Company). Her poems are widely anthologized, included in The Oxford Book of American Poetry and The Best of the Best American Poetry. Her latest work of nonfiction is The Paper Garden: Mrs. Delany Begins Her Life’s Work at 72 [warning: site autoplays audio], at once a biography of an extraordinary 18th century artist and a meditation on late-life creativity. She is the author of the memoir Paradise, Piece by Piece. One of the creators of New York’s Poetry in Motion program, she co-edited Poetry In Motion: One Hundred Poems From the Subways and Buses. She is also the editor of an anthology of essays, The Private I, and a book about reading poetry, How to Read a Poem and Start a Poetry Circle. She serves as a Faculty Mentor at the Spalding University Brief Residency MFA Program and as the Series Editor of The Best Canadian Poetry in English. |  |

| A dual citizen of the US and Canada, Molly Peacock is a former New Yorker who makes her home in Toronto with her husband, two cats, and a jam-packed terrace garden. I interviewed her for Couplets: a multi-author poetry blog tour. She was so generous in her answers that I’ve decided, at her suggestion, to break this interview into two parts: here is part two.

Joanne Merriam: When you read at Vanderbilt last year, you talked a little about what it was like to move to a new country from your birth country. I was particularly interested in that, because I’m a relatively new immigrant to the States from Canada. Can you comment on what it has meant to your writing to become Canadian, and how your American roots have also informed your writing? Molly Peacock: I was born in the States and the young woman I was, who gathered herself up and moved to New York City to write her sonnets, always in some ways writes my poems in her inquisitive, definitive American voice. But I came to Canada in mid-life, where I began to write prose. The mid-life woman, searching for a broader expression, curious about others, secure in her quirky perceptions, always emerges in my prose. Both these women live comfortably inside me. I cross the border between Canada and the US all the time. I keep two passports and two currencies in my wallet, and two bank cards, too! Part of my grandparents’ generation on both sides of my family had Canadian roots. I’m really a hybrid. Buffalo, where I was born, is smack up against the border. |

|

| And yet. I wonder what hybridized plants feel; I wonder what grafted fruit trees feel. If you are not a gardener or a farmer or a writer about horticulture, or a botanist, you might not think of the slow, defined movements of plants and their growth, but since I do write about plants, and I do think about horticultural things, I wonder about how they absorb their new homes as they are transplanted. I’m a transplant, yet I uproot myself, sometimes weekly.

But it is a strange life to be so dual. At this point in my life, I can’t give either country up. When the American border guard says, “Welcome home,” I think, “New York City! On what streets am I more at home?” But when I return to the high, gray skies of Toronto, walking into our apartment, I feel utterly at rest. “Where are you?” is the first question any of my friends asks me. In my little office looking out over Toronto, “I’m home,” I respond. In a literary way, where I am is a key question. I write in two genres, poetry and nonfiction, never giving one up for the other. My poetry has lost some of the anxiety I talk about in my answer to your next question, it’s much more free verse and less formal. I don’t always wear my city shoes. |

|

|

Joanne Merriam: I realize this is difficult ground, and Canada has at least two great poetic traditions to go with its two official languages (not to mention its long First Nations history), but can you comment on any general national characteristics of the poetry being produced by Canadians vs that being written by Americans? Molly Peacock: Absolutely. I can happily talk about poetry in English written by Anglophone Canadians, and that includes Anglophone aboriginal Canadians, too. Although I sometimes read Francophone Canadian poetry, I really don’t know enough about it to comment. The big difference between Canadian and American poetry in English is the trust in the reader. Canadian poets trust that their readers will stay with them. If the poets start slow, if they let their poems wander, they seem to feel that the reader will be patient, will come with them. The poets trust that, eventually, their careful, engaged readers will get why this oddball journey of the poem is going on. The Canadian poet and the Canadian reader walk into the lake of the poem together. |

|

| But in the U.S., that poet-reader contract is entirely different. The poet can’t trust the reader to be an ally. The poet has to show the reader from the very first line why the poem is worth that impatient, distracted reader’s time. The American poet has to start the poem on the highest diving board, then jackknife into the pool below. After the reader is wowed and amazed, then the poem proceeds. It’s an entirely different agreement, one in the pool, the other on the side watching. The lanky, longer, meditative-narrative of Canadian poetry proceeds entirely differently from the shorter lyric-narrative of American poetry.

Joanne Merriam: I’m amazed at how much you do to promote poetry, between all your teaching and lecturing engagements, co-creating Poetry in Motion, helping with Representative Poetry On Line, editing Best Canadian Poetry in English, and so on. What strategies do you feel work best in getting poetry in front of people who don’t usually read it, and what is it about poetry that drives you to champion it? |

|

| Molly Peacock: I grew up in a household where there were very few books except the Bible and Popular Mechanics Magazine. However, there were library books. Once a week my mother went to the library and got out a stack of novels which she gleefully ploughed through, almost one a day. So I got the idea that everyday people who weren’t educated and didn’t have the cash to buy books could enjoy them, appreciate them and educate themselves. My mother coming down the steps of the Kenmore Public Library and my father swinging his black metal lunch pail are permanent images in my mind, and the source, however eventually obscured, of all the public efforts I have made on behalf of poetry. I wanted them to read me. They never did. But luckily I had other readers, like you Joanne Merriam, and others at Vanderbilt University where our paths crossed. That impulse to gather and educate the potential readers of poetry has never left me. What strategies work? Oh, elbow grease! And enthusiasm. And persistence. And getting your friends absorbed in an idea you have—or joining others’ ideas. You can’t do it alone. Poetry itself isn’t written alone. That’s a myth. You need a friend’s encouragement, a friend’s ear. And you need that for reading, too. |  |

Check out more poetry-related interviews, reviews and guest posts at Couplets: a multi-author poetry blog tour.