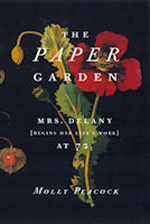

Molly Peacock is a poet, essayist and creative nonfiction writer. She has published six volumes of poems including Cornucopia: New and Selected Poems and, most recently, The Second Blush (both from W.W. Norton and Company). Her poems are widely anthologized, included in The Oxford Book of American Poetry and The Best of the Best American Poetry. Her latest work of nonfiction is The Paper Garden: Mrs. Delany Begins Her Life’s Work at 72 [warning: site autoplays audio], at once a biography of an extraordinary 18th century artist and a meditation on late-life creativity. She is the author of the memoir Paradise, Piece by Piece. One of the creators of New York’s Poetry in Motion program, she co-edited Poetry In Motion: One Hundred Poems From the Subways and Buses. She is also the editor of an anthology of essays, The Private I, and a book about reading poetry, How to Read a Poem and Start a Poetry Circle. She serves as a Faculty Mentor at the Spalding University Brief Residency MFA Program and as the Series Editor of The Best Canadian Poetry in English.

A dual citizen of the US and Canada, Molly Peacock is a former New Yorker who makes her home in Toronto with her husband, two cats, and a jam-packed terrace garden. I interviewed her for Couplets: a multi-author poetry blog tour. She was so generous in her answers that I’ve decided, at her suggestion, to break this interview into two parts: here is part one.

Joanne Merriam: You write many formal poems, especially sonnets, which are of particular interest to me right now since I’m spending the month of April working on sonnets, so (selfishly) I’ll start by asking about them. What is your writing process when you write a formal poem?

| Molly Peacock: Let’s begin with a little personal history of a writing process: I began writing sonnets in the late 1970’s when I was attending The Writing Seminars at The Johns Hopkins University. It wasn’t part of any course. My professors didn’t teach anything technical or “how to.†So I decided to teach myself. I’m a happy autodidact; the teacher MOLLY can let the student Molly learn at her own pace. First I had to teach myself to write in ten-syllable lines. Just counting syllables felt accomplished. I never wanted to write “exercises” or practice poems, so I integrated the syllable counting into my real poems, things I genuinely wanted to write. And I limited the number of lines to fourteen, though I didn’t always hit fourteen exactly. (I often overran both syllables and lines.) I’d congratulate myself at every bit of accomplishment, believing, along with Gertrude Stein, that it’s praise that moves an artist forward.

Then I started working on rhyme schemes, allowing myself any sound correspondences that felt right to my ear. I depended on my own ear for language. I knew I had a good internal ear, and that sound was connected to my deepest emotions, so I relied on that, even when what I heard seemed contradicted by what I thought of as “exterior” criteria, like formal meter. I didn’t seriously tackle meter for at least a decade, probably more. I so cherished that inner ear that I couldn’t bend the music in my head (and body) to what I thought of as an external marching order. But in fact many of my ten-syllable lines were pentameter lines. |

|

| I just let the formally metrical lines infiltrate and whirl around in the poem, mixing with the voice I had always depended on, my own voice, the working class Buffalo girl who was going to write “low” sonnets, using her own mix of both blue collar and high art images and sounds.

Just last week I visited the fabulous collection of abstract expressionists at the Albright Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo. It is so vigorous and inspiring. When I was in high school, in the early 1960’s, I took the bus from the little house in the suburbs where I grew up to the Art Gallery time after time, and I loved escorting myself to see that collection. Again, the teacher MOLLY was taking the student Molly on a little art trip. The reward for student Molly was to eat cinnamon ice cream in the Gallery restaurant in my dopey pleated skirt next to these glamorous art-y women with black hair and red lipstick. Somehow those images found their way inside me along with the vocal rhythms of my family. That was the mix of high and low I had in my sonnets. |

|

| But now, after decades of writing them, what is my process? I begin with the subject AND the form. If it’s a sonnet I intend, I don’t try to make something else I abandoned into a sonnet. And I work and work on the first line so it sits right. The first step determines all the rest. I don’t over-manage the rhymes. I ease into them with the syntax. If a sound doesn’t ease in, I turn to another rhyme. I never use a rhyming dictionary. All the sounds must come from the interior. I do make lists of rhymes and I write them either on the side of the page if I’m writing on a violet or a blue legal pad, or on the opposite page if I’m writing in a book-size, bound notebook. (I write all first drafts of poems by hand, obviously, but then I type them into my computer and continue the drafts on the computer.) If the meter doesn’t fall into smooth units, I don’t worry too much about it until later. If I use the same vocabulary over and over, I don’t worry about that either, if it’s in the middle of the line. I can fix that later.

I don’t always know what the sonnet will be about. I have a kind of image in my head, something I might like to paint, if I were a painter, or a thought, but not something entirely thought through. If I intended a Shakespearean sonnet, and it’s not working out, I change to a Petrarchan sonnet, and if that doesn’t work out, I turn to a nonce form, something I can make up. It’s NOT about sticking to a form. It’s about balance and flexibility. I depend on my unconscious because the unconscious is always interconnected and full of correspondences. I don’t worry about it being present there for me. It’s always present there for me, whether I like it or not! Form and content are working together; it’s both planned and surprising. I’m working, engaged, intent, over-focused, as if I had to plant a lot of seedlings while the soil was wet and the sun not too high. I’m enjoying myself. Sailing on the lake of it. The outside world is nothing to me. And the poem is forming under my hands, my whole body over it, around it. |

|

Check out more poetry-related interviews, reviews and guest posts at Couplets: a multi-author poetry blog tour.